1993년 소득 조건부 상환(ICR)으로 시작된 소득 기반 학자금 대출 상환 계획은 학자금 대출 상환을 소득의 특정 비율 이하로 제한함으로써 많은 차용인에게 월 상환을 훨씬 더 저렴하게 만들 수 있습니다. 그러나 5가지 소득주도상환(IDR) 계획 중 하나를 고려할 때 차용인이 월별 상환 비용을 관리할 수 있는 방법뿐만 아니라 차용인의 장기 소득 궤적을 생각하는 것이 중요합니다. 지불은 소득을 기반으로 하기 때문에 높은 미래 소득을 기대하는 사람들은 IDR 계획을 사용하여 혜택을 받지 못할 수 있습니다. 지불액은 소득 수준에 비례하여 증가하기 때문에(그리고 상환되는 대출의 이자율에 따라) 차용인은 높은 지불액으로 빠르게 대출금을 상환하는 것보다 낮은 월 지불액을 유지하는 것이 더 나을 수도 있고 그렇지 않을 수도 있습니다. 이로 인해 IDR 계획을 선택하는 결정이 잠재적으로 복잡해집니다. 특히 연방 학자금 대출에 대한 많은 상환 계획이 소득 대비 월 상환액을 제한할 뿐만 아니라 실제로 특정 년 후에 대출 잔액의 면제를 유발할 수도 있기 때문입니다.

따라서 차용인이 학자금 대출 부채와 잠재적 상환 전략을 다루는 첫 번째 조치는 구체적인 목표를 식별하는 것입니다. 가능한 한 빨리 대출금을 전액 상환하고 이자 비용을 최소화하는 것입니다.> 도중에 또는 대출 용서를 구하고 총 지불액을 최소화할 수 있습니다. 도중에 (용서 기간이 끝날 때 용서되는 금액을 최대화하기 위해). 목표가 명확해지면 계획자는 사용 가능한 상환 옵션을 탐색할 수 있습니다.

대출 탕감의 길을 찾는 사람들에게는 현재 지불 의무를 제한하는 IDR 계획이 종종 선호됩니다. 왜냐하면 그것이 대출이 마이너스 상각으로 이어지더라도(차용인이 대출을 받은 경우 학자금 대출에 대한 이자가 필요한 상환액을 크게 초과할 수 있기 때문입니다.) 상대적으로 낮은 수입), 그렇게 하면 결국 용서가 극대화됩니다. 반면에 빚 탕감이 최선이 아닐 수도 있습니다. 차용인이 탕감(일반적으로 20년 또는 25년)을 통해 해당 IDR 계획을 계속 유지하는 경우 탕감된 금액은 세금 목적상 소득으로 처리될 수 있습니다(일부 차용인의 경우 실제로 총 비용이 실제보다 훨씬 더 높을 수 있습니다. 실제로 대출 잔액을 $0로 낮추었다면 지불했을 것입니다!).

궁극적으로 요점은 가계 현금 흐름을 관리하려는 욕구가 용서를 최대화하는 지불을 최소화하는 것을 수반하지만 소득이 증가함에 따라 상환 의무가 증가하고 용서의 소득세 결과는 때때로 총 차입금을 증가시킬 수 있기 때문에 상환 전략을 신중하게 선택해야 한다는 것입니다. 가능한 한 빨리 대출금을 상환하는 것보다 비용이 많이 듭니다!

Ryan Frailich는 30대 커플, 교육자 및 비영리 단체 직원과 함께 일하는 것을 전문으로 하는 유료 재무 계획 업체인 Deliberate Finances의 설립자인 CFP입니다. 플래너가 되기 전에 Ryan은 교사로 일한 후 Talent &Human Resources의 이사로 차터 스쿨 조직을 성장시키기 위해 일했습니다. 나이와 직업을 감안할 때 학자금 대출은 대부분의 고객에게 우선 순위이므로 고객에게 학자금 대출 옵션에 대한 정보를 제공하는 올바른 방법을 찾는 데 많은 시간을 할애했습니다. Twitter에서 그를 찾거나 ryan@deliberatefinances.com으로 이메일을 보내거나 기본적으로 맛있는 음식과 음료를 제공하는 모든 뉴올리언스 축제에서 그를 찾을 수 있습니다.

연방 정부는 일반적으로 대출을 받은 시기, 대출을 받은 사람 및 대출 목적에 따라 다양한 다양한 프로그램에 따라 수십 년 동안 교육 기반 대출을 제공했습니다. FFEL(Federal Family Education Loan) 프로그램은 2010년까지 대출의 가장 일반적인 출처였으나 이후 의료 및 교육 화해법(Healthcare &Education Reconciliation Act)은 해당 프로그램을 단계적으로 폐지했습니다. 오늘날 모든 연방 정부 대출은 단순히 "직접 대출"이라고 하는 William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan 프로그램을 통해 제공됩니다.

전통적으로 직접 및/또는 FFEL 대출을 받은 차용인이 학교를 떠날 때 일반적으로 대출 상환이 없는 6개월의 유예 기간이 있습니다. 그러나 6개월의 유예 기간이 지나면 차용인은 10년 표준 상환 계획에 따라 월별 상환액이 해당 이자율로 120개월에 걸쳐 상각된 미지급 부채를 기준으로 합니다.

그러나 많은 차용인들이 10년 표준 상환 일정에 따라 정해진 상환금을 감당할 수 없습니다. 특히 학자금 대출과 관련하여 차용인이 학교를 마치기 전에 대출(및 상환 의무)이 발생하고 자신이 어떤 직업을 갖고 있는지 알아낼 때 '합리적인'(또는 실현 가능한) 상환 의무가 무엇인지 달리 결정하는 것이 어렵다는 점을 인식합니다. 우선 얻을 것입니다 (그리고 그들이 벌게 될 수입). 이러한 불확실성을 감안할 때 정부는 관리 가능한 상환 조건을 용이하게 하기 위한 또 다른 옵션으로 소득주도상환(IDR) 계획을 도입했습니다.

소득주도상환(Income-Driven Repayment, IDR) 계획은 모두 동일한 전제를 가지고 있습니다. 단순히 이자율과 주어진 상각 기간을 기준으로 대출에 대한 상환 의무를 설정하는 것이 아니라 상환 의무를 차용인 임의 소득의 백분율로 계산합니다( 일반적으로 조정된 총소득 및 연방 빈곤 지침을 기반으로 함).

따라서 학자금 대출 IDR 계획을 추구하는 차용인은 매년 소득(및 가족 규모)을 재인증하기 위한 서류를 제출해야 하며, 이후 월별 대출 지불액은 소득 수준에 따라 조정됩니다. 이는 학자금 대출 상환 의무 자체가 가계에 대해 '실행 가능한' 상태로 유지되도록 하는 데 도움이 될 뿐만 아니라 대출을 불이행할 수 있는 사람들이 대출을 양호한 상태로 유지하고 신용 점수를 유지할 수 있도록 합니다.

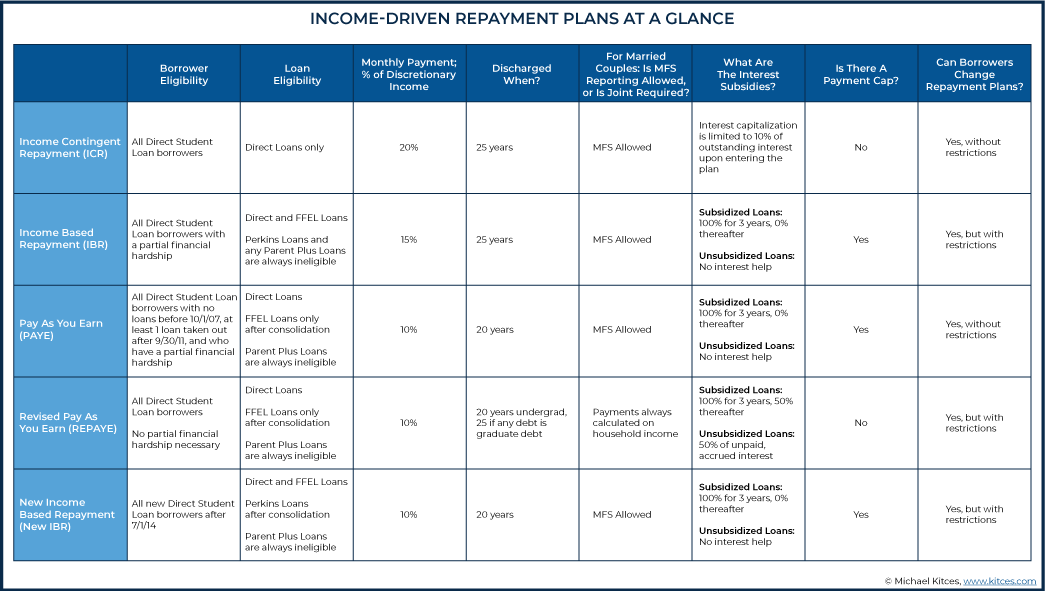

그러나 실제로는 다양한 IDR 계획에 대한 개별 규칙이 크게 다르며 각 상환 계획이 8가지 주요 기준에 따라 다르기 때문에 최상의 IDR 계획을 선택하는 것이 어려울 수 있습니다.

앞서 언급한 각 기준에 대한 각 IDR 계획 옵션과 해당 규칙을 살펴보겠습니다.

소득 조건부 상환(ICR) 계획은 최초의 IDR 계획 중 하나로 1993년에 시작되었습니다. 특히, 이 계획이 처음 도착한 이후로 다른 IDR 계획이 차용인에게 더 관대해졌기 때문에 ICR은 오늘날 선택되는 상환 계획이 거의 없습니다.

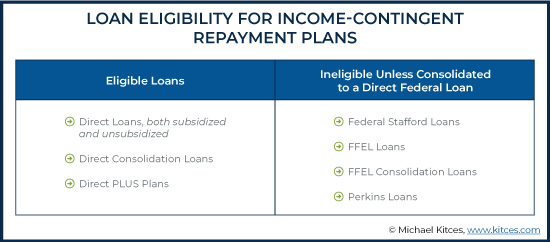

예를 들어, ICR은 가장 높은 월별 IDR 대출 지불 금액을 요구하고, 상환 계획 전반에 걸쳐 가장 낮은 수준의 이자 자본화를 수용하고, 직접 대출만 상환할 수 있도록 허용합니다(연방 스태포드 대출, FFEL 대출, FFEL 통합 대출 및 Perkins 대출은 적격하지 않음). ICR에 대한 대출 유형의 경우 직접 연방 대출로 통합되는 경우 자격을 얻을 수 있습니다.

하지만 다행히도 ICR에는 계획 변경에 대한 제한이 없기 때문에 차용인이 더 유리한 상환 계획을 선택하는 것이 비교적 간단합니다(차입자가 상환 계획을 변경할 때마다 미지불 이자는 자본화됨).

즉, ICR이 현재 이용 가능한 가장 관대하지 않은 플랜이지만 ICR에 대한 소득 요건이 없기 때문에 다른 IDR 플랜에 비해 더 많은 사람들이 이 플랜을 받을 수 있습니다.

ICR에 대한 연간 지불 금액은 차용인의 임의 소득의 20%를 계산하여 결정됩니다(ICR의 경우에만 조정된 총소득에서 차용인 가족 규모에 대한 연방 빈곤선의 100%로 정의됨).

기술적으로 차용인의 소득에 맞게 조정된 12년 고정 대출에 대한 지불 금액을 기반으로 하는 또 다른 계산이 있지만 이 방법을 사용하는 금액은 항상 위의 첫 번째 옵션보다 크므로 실제로 이 계산은 다음과 같습니다. 사용된 적이 없습니다.

그러나 ICR에 따른 상환 금액은 고정적이지 않으며 소득이 증가함에 따라 ICR 월별 지불액도 증가합니다. 없음 증가할 수 있는 한도. 따라서 ICR은 대출 기간 동안 소득이 극적으로 증가할 것으로 예상하는 차용인에게 최선의 선택이 아닐 수 있습니다.

ICR 계획은 원래 결혼한 차용인이 나머지 가족과 분리하여 단독으로 소득을 보고하는 것을 허용하지 않았지만 이후 계획이 수정되어 MFS 세금 신고 상태를 사용하여 보고된 소득을 사용할 수 있습니다.

ICR 플랜에서 25년 동안 지불한 후에는 대출 잔액이 탕감됩니다. 해당 탕감 금액은 탕감 금액에 대해 과세 대상 소득으로 간주됩니다(잔액 원금과 대출에 발생한 이자를 모두 포함).

ICR 계획은 계획에 처음 가입할 때 대출에 대한 미지급 이자의 최대 10%(원금 대출 잔액에 추가됨)를 자본화하는 것 이상의 이자 보조금을 제공하지 않습니다.

소득 기반 상환(IBR) 계획은 필요 기반 상환 계획으로 2007년에 수립되어 처음으로 부분 재정적 어려움 요건을 도입했습니다. 차용자는 2009년 7월에 IBR 계획을 처음 사용할 수 있었습니다.

Studentloans.gov 웹사이트에 따르면 "부분적 재정적 어려움"은 다음과 같이 정의됩니다.

특히, IBR 계획은 "부분적 재정적 어려움"을 차용인이 우선 소득 비율 제한에서 필요로 하고 혜택을 받을 정도로 높은 지불금을 받는 것 이상으로 정의하지 않습니다.

또한 자격에 대한 IBR의 "재정적 어려움"은 임의 소득의 15%만 초과하는 지불로 정의되기 때문에(IBR 및 ICR을 제외한 모든 상환 계획의 경우 임의 소득은 AGI와 해당 연방 빈곤선의 150%의 차이입니다. ), 재량 소득의 20%로 지불을 제한하는 ICR 계획과 비교할 때 ICR 및 최신 IBR 계획에 대한 자격이 있는 사람은 일반적으로 IBR 계획을 선택합니다.

앞서 언급했듯이 IBR 계획을 사용하는 차용인은 부분적인 재정적 어려움이 있어야 합니다. 자격 및 상환 금액을 결정하는 두 가지 유용한 도구는 다음에서 찾을 수 있습니다.

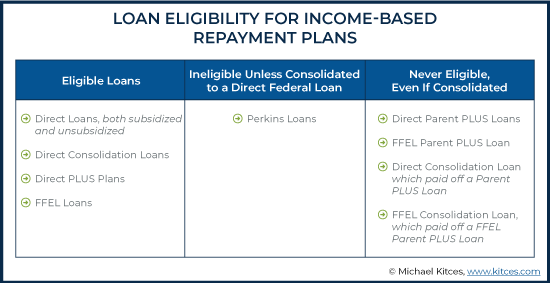

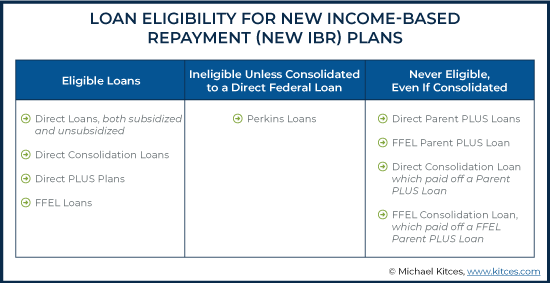

보조금 및 비보조 직접 대출, 직접 통합 대출, Direct PLUS 플랜 및 FFEL 대출 모두 IBR 플랜에 적격합니다. Perkins Loans는 직접 대출로 통합된 경우 자격이 있을 수 있지만, 모든 Parent PLUS 대출은 직접 대출로 통합된 경우에도 자격이 없습니다(즉, Parent PLUS를 상환하는 데 사용된 직접 통합 대출 및 FFEL 통합 대출을 의미합니다. 대출은 IBR 계획에 적합하지 않습니다.

연간 IBR 지불 금액의 공식은 차용자의 임의 소득의 15%만을 기준으로 하고 빈곤선의 150%(ICR의 경우 100% 대신)를 사용하여 계산한다는 점을 제외하고는 ICR 지불의 공식과 매우 유사합니다. 임의 소득 수준.

또한, IBR 계획에 대한 지불은 차용자가 IBR에 진입한 순간에 10년 표준 계획에 진입했을 때 지불했을 것보다 클 수 없습니다. 이렇게 하면 미래에 소득이 극적으로 증가할 위험이 제한되지만 미래에 필요한 지불 풍선도 더 커질 수 있습니다.

IBR 계획은 또한 차용인이 다른 가계 소득과 별도로 소득을 보고하는 것을 허용합니다. 즉, 결혼한 차용인이 MFS 상태를 제출하여 한 배우자 소득의 낮은 기준에 소득 비율 임계값을 적용하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

IBR에 따른 미지불 대출 잔액은 25년 동안 지불한 후 탕감됩니다. 다른 모든 IDR 계획과 마찬가지로 용서 금액은 과세 소득으로 간주됩니다.

이자 보조금과 관련하여 교육부(DOE)는 보조금을 받는 대출에 대해 처음 3년 동안 미지급된 모든 이자를 보장합니다. 무보조 대출 및 보조 대출의 경우 최초 3년이 경과한 경우 이자가 보조되지 않습니다.

IBR 계획에서 다른 상환 계획으로 전환하기로 결정한 차용자는 몇 가지 제한 사항을 염두에 두어야 합니다. 즉, 최소 1개월 동안 10년 표준 상환 계획을 체결해야 합니다. 또는 최소 1회 감면 상환(차용인이 대출을 "인계" 상태로 전환하여 대출 상환 금액을 일시적으로 효과적으로 줄인 다음, 새로운 IDR 계획으로 전환하기 전에 유예 기간 동안 한 번만 상환할 수 있는 경우). 감액된 연체료는 대출 기관과 협상할 수 있으며 잠재적으로 매우 낮을 수 있습니다. 또한 차용인이 상환 계획을 변경할 때마다 미지급 이자가 자본화됩니다.

Pay As You Earn(PAYE)은 2012년 10월 자격을 갖춘 차용인이 사용할 수 있게 되었으며, 대학 등록금이 치솟는 새 차용인에게 약간의 구제책을 제공할 목적으로 제공되었습니다(많은 이전 차용인에게 제공되지는 않았지만).

IBR 계획과 마찬가지로 PAYE는 차용인에게 부분적인 재정적 어려움(특정 소득 비율 임계값을 초과하는 학자금 대출 상환으로 다시 정의됨)을 요구합니다. 또한 차용인은 2007년 10월 1일 현재 학자금 대출 잔액이 없어야 하고 2011년 10월 1일 이후에 지급된 연방 학자금 대출이 하나 이상 있어야 합니다(즉, 최근에 학자금 대출 차용자가 되어야 함).

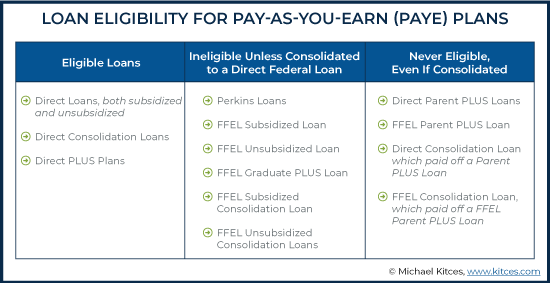

PAYE 상환 계획은 보조금 및 비보조 직접 대출, 직접 통합 대출 및 Direct PLUS 계획을 모두 수용합니다. Perkins Loans 및 모든 FFEL Loans는 부적격이지만 Direct Federal Loan으로 통합된 경우 자격을 얻을 수 있습니다. FFEL Parent PLUS 대출 외에도 Direct Parent PLUS Loans 및 Direct Consolidation Loan을 상환한 Parent PLUS Loan도 받을 자격이 없습니다. PAYE 요금제.

연간 PAYE 지불 금액은 차용인 임의 소득의 10%와 동일하며 ICR(임의 소득의 20%) 및 IBR(임의 소득의 15%)보다 낮습니다. IBR 지불과 유사하게, PAYE 플랜 지불 금액은 차용인이 PAYE를 입력한 순간에 10년 표준 플랜에 들어왔을 때 지불했을 것보다 클 수 없습니다. 이렇게 하면 누군가의 소득이 극적으로 증가하여 필요한 지불 풍선도 더 커질 위험이 다시 제한됩니다.

ICR 및 IBR과 마찬가지로 PAYE 차용인은 MFS 신고 상태를 사용하여 소득을 별도로 보고할 수 있습니다.

PAYE의 경우 미결제 대출 잔액은 20년의 지불 후에 탕감됩니다. ICR 및 IBR 계획의 탕감 기간이 25년이 더 긴 것과는 대조됩니다. 총 탕감 금액은 과세 소득으로 간주됩니다.

이자 보조금은 IBR을 사용하는 차용인의 경우와 동일합니다. 보조금을 받는 대출의 경우 교육부(DOE)에서 처음 3년 동안 미지급된 모든 미지급 이자를 부담합니다. 무보조 대출(및 최초 3년 이후의 보조 대출)의 경우 이자가 보조되지 않습니다.

차용자는 제한이 없고(예:ICR 계획에서 전환) 다른 연방 상환 계획으로 쉽게 변경할 수 있으며, 일정 기간 동안 10년 표준 계획을 유지해야 하는 요구 사항도 없습니다. 그러나 차용인이 상환 계획을 변경할 때마다 미지불 이자는 자본화됩니다.

Revised Pay As You Earn(REPAYE) 계획은 2015년 12월 차용인에게 제공되었으며 PAYE의 관대한 조건의 혜택을 받을 수 있는 적격 차용자 목록으로 확대되었습니다(적어도 ICR 및 IBR 계획과 비교할 때 PAYE보다 지불 금액이 더 많고 용서 기간이 더 깁니다.

그러나 REPAYE는 PAYE에 비해 몇 가지 중요한 단점이 있습니다. 특히, REPAYE는 기혼 차용인이 가구 소득과 별도로 개인 소득을보고하는 것을 허용하지 않는 유일한 상환 계획입니다. 차용인이 MFS 상태를 사용하여 세금을 신고하더라도 지불은 총 가구 소득을 기준으로 합니다. 이것은 배우자가 그들보다 훨씬 더 많이 버는 차용인에게 REPAYE를 훨씬 덜 매력적으로 만듭니다.

'최근' 학자금 대출 대출자(2011년 이후 지출된 대출자)만 사용할 수 있는 PAYE 계획과 달리 REPAYE는 모든 연방 학자금 대출 차용인은 대출을 언제 받았는지 또는 부분적으로 재정적 어려움을 겪고 있는지에 관계없이. 즉, 2011년 이전 대출이 있어 PAYE 플랜 자격이 없는 차용인은 여전히 REPAYE 상환 플랜으로 전환할 수 있습니다.

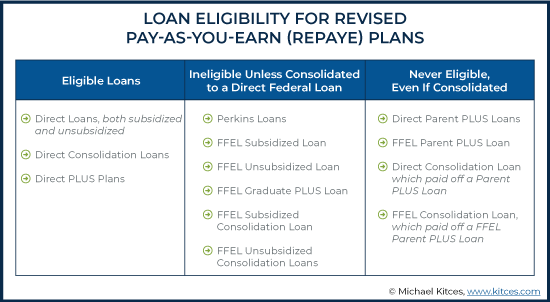

PAYE에 대한 적격(및 부적격) 대출은 REPAYE의 대출과 동일합니다.

REPAYE 지불 금액은 PAYE 금액과 동일합니다(차입자 임의 소득의 10%). 그러나 PAYE와 달리 지불액을 늘릴 수 있는 한도가 없기 때문에 지불액은 다른 상환 계획에서 차용인의 한도를 훨씬 넘어 성장할 수 있습니다. 이로 인해 RPAYE는 미래 소득 능력이 훨씬 더 높은 차용인에게 위험이 됩니다(따라서 미래 소득과 함께 미래 지불 의무가 증가하여 원하는 경우 미래에 탕감받을 잔액을 보유하는 능력이 제한됨).

REPAYE 계획의 경우 모든 대출이 학부 대출인 경우 20년 동안의 상환(예:PAYE) 후 미결제 대출 잔액이 면제됩니다. 그러나 대학원 대출이 있는 경우 면제 기간은 IBR 및 ICR과 같이 25년입니다. 이러한 용서 금액은 과세 소득으로 간주됩니다.

REPAYE 계획에 대한 이자 보조금은 다른 상환 계획보다 확대되고 더 관대합니다. 보조금이 지급되는 직접 대출의 경우 교육부는 REPAYE 계획을 체결한 후 처음 3년 동안 미지급 이자의 100%를 계속해서 충당합니다. 이것은 PAYE 및 IBR 계획(원래 및 신규 IBR 계획 모두)의 경우에도 해당되지만 REPAYE의 고유한 점은 3년 후에도 교육부가 미지급 대출이자의 50%를 계속 보조금을 지급하는 반면 다른 계획( 플랜 진입 후 이자를 지원하지 않는 ICR을 제외하고) 3년 후에는 이자를 지원하지 않습니다. 또한, REPAYE 플랜은 보조금이 없는 대출에 대해 이자 지원을 제공하지 않는 다른 플랜과 달리 보조금이 없는 직접 대출에 대해 미지급, 미지급 이자의 50%를 보조합니다.

또한, REPAYE에서 다른 상환 계획으로 전환하는 것은 PAYE에서 전환하는 것만큼 간단하지 않습니다(제한 없음). REPAYE에서 변경하는 차용자는 IBR에서 변경하는 것과 동일한 제한 사항에 직면합니다. 즉, 최소 1개월 동안 10년 표준 요금제를 체결해야 합니다. 또는 최소한 한 번은 감액된 유예비를 지불합니다. 다시 말하지만, 감소된 유예 지불 금액은 대출 기관과 협상할 수 있으며 잠재적으로 매우 낮을 수 있습니다.

모든 경우에 차용인이 상환 계획을 변경할 때마다 미지급 이자가 자본화됩니다.

새로운 IBR 계획은 2010년 의료 및 교육 조정법의 일부로 통과되어 2014년에 사용 가능하게 되었습니다. 이 계획은 필요한 지불금을 낮추고 용서 기간을 단축함으로써 이전에 사용 가능한 각 계획의 가장 관대한 측면 중 일부를 결합합니다. , 그리고 MFS 세금 신고 상태의 사용을 허용합니다.

그러나 가장 차용인에게 친숙한 계획이지만 유일한 자격이 있는 사람은 아직 거의 없습니다. 최근 학자금 대출을 받을 수 있는 자격이 있으며 이전 학자금 대출을 받은 사람으로 전환할 수 없습니다. 신규 IBR 플랜은 2014년 7월 1일 현재 대출 잔액이 없으나 기존 IBR 플랜과 동일한 대출 상환을 제공하는 차용자에 한합니다.

새로운 IBR 지불은 더 낮은 비율의 소득을 지불해야 한다는 점에서 기존 IBR 지불과 다릅니다. 기존 IBR 계획은 차용인 임의 소득의 15%를 기반으로 하지만 새로운 IBR 지불 금액은 차용인 임의 소득의 10%에 불과합니다(PAYE 및 REPAYE 지불 금액과 동일). 이전 IBR 계획과 마찬가지로 새 IBR 계획은 차용인이 계획에 들어간 순간에 10년 표준 계획에 입력했을 때 지불했을 것보다 클 수 없으므로 소득 수준이 증가함에 따라 상환 금액이 급격히 증가할 위험을 제한합니다.

New IBR 플랜의 경우 미결제 대출 잔액은 기존 IBR에서 요구하는 25년보다 짧은 20년 지불 후 탕감됩니다. 그 용서는 과세 소득으로 간주됩니다.

이자 보조금에 관해서는 원래 IBR 계획과 동일하게 유지됩니다. 교육부는 보조금을 받는 대출에 대해 처음 3년 동안 미지급된 모든 이자를 충당합니다. 무보조 대출 및 처음 3년이 지난 보조금 대출의 경우 이자 지원이 없습니다.

New IBR에서 전환하려는 차용인의 경우 최소 1개월 또는 동안 10년 표준 계획을 체결해야 합니다. make at least one reduced forbearance payment, which can be negotiated with the loan servicer (and can potentially be very low). Any outstanding, unpaid interest when switching plans will be capitalized.

Given all the variation in rules across IDR plans, required minimum payments can vary significantly depending on the situation.

Let’s look at an example.

Corey the Attorney

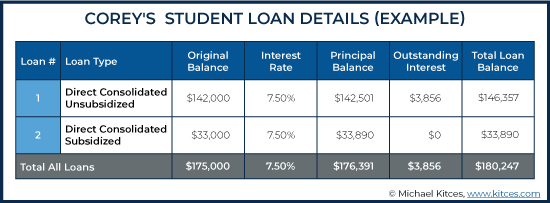

Corey is a young attorney with a current student loan balance consisting of $176,391 principal + $3,856 interest =$180,247 at a 7.5% annual interest rate.

After graduating, Corey could not afford the required payments under the 10-Year Standard Plan and switched to a REPAYE plan. Upon doing so, his outstanding loan interest was capitalized and added to his principal balance.

Corey suspects that REPAYE might not be the best plan for him, and seeks help from his financial advisor to determine what his best course of action would be to manage his loan repayments most effectively.

Corey earns an annual salary of $120,000. After his 401(k) contributions and other payroll deductions, his AGI is $105,000. Based on the state in which Corey lives, 150% of his Poverty Line (for a family size of 1) is $18,735, which means his discretionary income is $105,000 - $18,735 =$86,265.

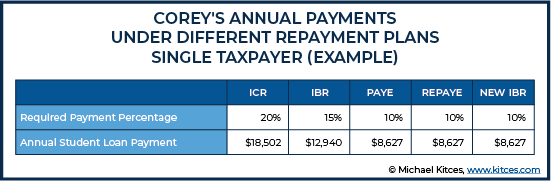

Under Corey’s original 10-Year Standard Repayment plan, Corey was required to make annual payments of $24,924. Under the IDR plans, however, his monthly payments would be significantly lower, with forgiveness of the outstanding balance after 20-25 years.

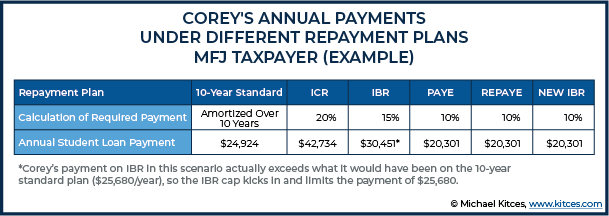

The table below shows Corey’s annual payments for each of the IDR plans:

The range of payments available to Cory across the plans is substantial, more than $8,600 in the first year alone (between $17,253 for ICR and $8,627 for PAYE, REPAYE, and the New IBR plans), assuming that he is eligible for all options, which may not always be the case. Notably, as the plans become more current, they also become more generous with lower payment obligations.

Corey has indicated that he plans to marry and adopt a child in the next year and that his soon-to-be spouse currently has an AGI of $130,000. With the larger income and larger family size, his options are updated as follows, assuming the family will be filing their taxes jointly:

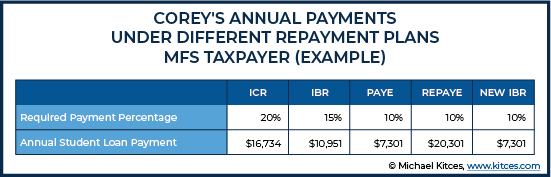

While the gap between IBR and the other options is starting to grow, using MFS as a tax-filing status can reduce his payments for some of the plans even further. If Corey were to use an MFS Status, his options would be as follows:

Here we see where the inability to use MFS with REPAYE can be harmful to someone who is about to get married, as staying on REPAYE would require joint income to be used to calculate discretionary income, resulting in a substantially higher required payment.

While the New IBR option is very appealing, upon checking Corey’s loan records, his advisor discovers that some of his loans originated before 2014, which excludes him from eligibility as borrowers using New IBR may not have any loan balances prior to July 2014.

Thus, payments on IDR plans for Corey will initially range from $7,301 (under PAYE filing MFS) to $42,734 (using ICR filing MFJ) in annual payments. While this would be the expected range for at least the first few years of the repayment plan, life events pertaining to family size, tax filing status, and income levels can come up that may impact Corey’s student loan repayment amounts.

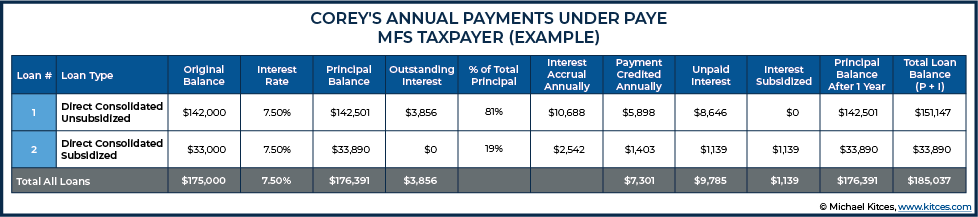

At first glance, it seems clear that Corey should use PAYE and file MFS next year since that would produce the lowest possible monthly payment. But that could have a significant downside since interest accrual will be larger every year than the required payments if he were to choose PAYE. Which plays out into what is known as “negative amortization”, where the principal-and-interest balance amortizes higher as the excess unpaid interest accrues and compounds.

Under normal student loan rules, required payments get split and applied to loans in proportion to the total balance owed. So, in this case, the required payment of $7,301 annually will be applied 81% to the unsubsidized loan, and 19% to the subsidized loan.

If Corey elects to use PAYE and MFS as a tax status, he’ll see his smaller, subsidized student loan principal stay steady in years 1-3 due to the PAYE interest subsidy, but the larger, unsubsidized loan balance will have grown, and his payments of $7,301 this year will have resulted in a balance $4,790 greater than a year ago. Beyond the first 3 years, the interest subsidy is lost, and he’ll see his balance grow for both of the loans.

If his future income growth is low, this plan might make sense, as it would keep his monthly payments low. Using assumptions of 3% income growth and federal poverty level growth, and staying on this exact plan for 20 years, the total principal + interest at forgiveness is $315,395. If we apply a 30% effective tax rate, he will incur just under $95,000 of taxes. If we add the $95,000 of taxes to the $196,000 of payments he made over 20 years, we get to a total loan cost of $290,786.

Corey’s financial advisor compares these numbers to privately refinancing the debt to get a better interest rate. If Corey is approved for a 15-year loan at a 5% interest rate, his monthly payments would be $1,425 with a total loan cost of $256,568. With the help of his advisor, Corey determines that the monthly payment amount under this refinanced loan can be comfortably paid amongst other goals and chooses to pursue the 15-year private refinance option. Under this plan, Corey will pay down the debt sooner (15 years, versus 20 years under PAYE filing MFS until forgiveness) and will pay less in total costs along the way. In addition, he can eliminate the uncertainty (and anxiety) of seeing a constantly growing loan balance, and actually see progress to $0 being made along the way.

Negative amortization isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker. It goes back to whether the intention is to pay off the loan in full, or, to go for some form of forgiveness. In reality, for those who do plan to aim for forgiveness, it actually makes sense for the borrower to do everything they can to minimize AGI, not only resulting in lower student loan payments but also having a higher balance forgiven. This can make sense both for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF), where the balance is forgiven after 120 payments (10 years) and is not taxable and also for a borrower going towards the 20- or 25-year forgiveness available under one of the IDR plans.

I regularly see people who make $50,000 - $70,000 per year with loan balances over $100,000. For a resident physician, who will see their income dramatically rise, an IDR plan (usually PAYE or REPAYE) makes sense to make payments manageable while in residency, even if it means a small amount of negative amortization on their loans. Their ability to repay the loans once they have their full doctor salary means that going for long-term forgiveness rarely makes sense, but the IDR plan can help them manage cash flow during the tight income years as a resident for a relatively modest cost (of negatively amortized interest).

Many borrowers with early-career income levels similar to a resident may not have the same expectations for substantial long-term earnings growth in their future. For these individuals, pursuing long-term forgiveness using an IDR plan may be a more advantageous option. In other words, negative amortization isn’t just used to incur a small amount of interest to be repaid in the future when income rises, but a potentially larger amount of negatively amortizing interest that will ultimately be forgiven altogether.

다른 예를 살펴보겠습니다.

Shannon the Acupuncturist

Shannon is a 28-year-old who runs her own acupuncture business. Other important details about her situation include:

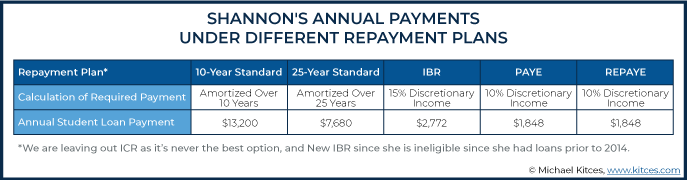

Here are her repayment options:

The 10-Year Standard plan would require her to pay $13,200 annually (over $1,100/month), which is clearly not feasible. She could instead choose to repay with a 25-Year Standard Repayment plan, but Shannon would end up paying nearly $192,000 over that time and the $640 monthly payment would also be infeasible unless she stopped contributing to retirement accounts.

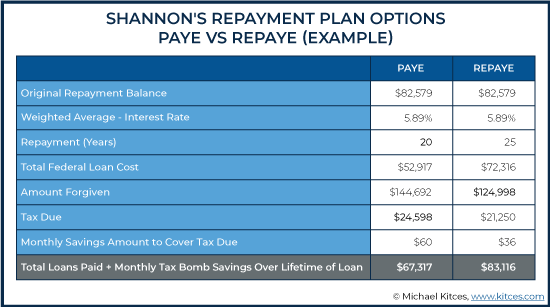

Since she is eligible for PAYE and REPAYE, neither IBR nor ICR makes sense, as each has higher required payments. So, she will decide between PAYE or REPAYE, each of which requires her to pay 10% of her Discretionary Income, or $154 per month at her current income level.

The interest subsidies on REPAYE are better, as while both PAYE and REPAYE will subsidize 100% of Shannon's unpaid interest on her loan during the first three years of the plan, REPAYE will continue to subsidize 50% of unpaid interest afterward whereas PAYE will not subsidize interest after three years. Thus, the growth of Shannon’s balance due to an increasing interest balance will be limited with REPAYE.

Using PAYE, however, will result in loan forgiveness in 20 years instead of in 25 years under REPAYE.

Either way, the so-called ‘tax bomb’ must also be accounted for, since the forgiven loan balance will be treated as taxable income received in the year the loan is forgiven. Borrowers pursuing any IDR plan should plan to cover that tax, and in this case, Shannon can do so with relatively small monthly contributions to a taxable account.

To sum it all up, to repay her loans in full on a 25-Year Standard Repayment plan, Shannon likely would have to pay $640 per month, at a total repayment cost of $192,000.

On REPAYE, she would start with payments of $154/month based on her Discretionary Income and, factoring for inflation, top out in 25 years at $343/month. She would owe a total repayment amount of $72,316 in loan costs + $21,250 in taxes =$93,566.

If she chooses PAYE, she would have starting payments of $154/month (also rising to $295 with AGI growth over 20 years), with a total repayment amount of $52,917 in student loan costs + $24,598 in taxes =$77,515. She would also finish in 20 years (versus 25 years on REPAYE).

Assuming all goes as planned, PAYE appears to be the better choice, as even though REPAYE provides more favorable interest subsidies, Shannon’s ability to have the loan forgiven 5 years earlier produces the superior result.

But what if her situation changes, as life does tend to happen that way?

If Shannon got married, and her spouse made substantially more than her, she may have to use MFS to keep her payments lower, and thus lose out on any income tax benefits available filing as MFJ.

Shannon also runs the risk of having to repay a higher balance in the future if she switches careers; in this situation, using PAYE for the 20-year forgiveness benefit would no longer make sense. Say she takes a new job resulting in AGI of $110,000 annually, and she takes that job 5 years into being on the PAYE plan.

Instead of repaying the original balance she had at the outset of opting into the PAYE plan, she would need to pay back an even higher balance due to growth during the years on PAYE, when payments were smaller than interest accrual resulting in negative amortization. As her salary rises, her payments would also rise so substantially (up to $747 here), that her total repayment cost to stay on PAYE for 15 additional years would actually be more than it would be to simply pay the loan off.

If she decides to reverse course and pay off the loan balance instead of waiting for forgiveness, she might instead benefit from a private refinance if she can get a lower interest rate, since that now once again becomes a factor in total repayment costs.

In the end, IDR plans have only been recently introduced, and as such, there is very little historical precedent regarding their efficacy for relieving student loan debt, particularly with respect to the income tax ramifications of student loan debt forgiveness. As in practice, ICR has rarely been used for loan forgiveness (difficult as the percentage-of-income payment thresholds were typically high enough to cause the loan to be repaid before forgiveness anyway), and the other IDR plans have all been rolled out in the past decade.

Accordingly, we won’t see a critical mass of borrowers reaching the end of a 20- or 25-year forgiveness period until around 2032 (PAYE) and 2034 (IBR). And will then have to contend for the first time, en masse, with the tax consequences of such forgiveness. Though forgiven loan amounts are taxable income at the Federal level, it is notable that Minnesota has passed a law excluding the forgiven amount from state taxes.

Similar to other areas of financial planning, it’s prudent to plan under the assumption that current law will remain the same, but also to be cognizant that future legislation may change the impact of taxable forgiveness. By planning for taxation of forgiven student loan debt, advisors can help their clients prepare to pay off a potential tax bomb; if the laws do change to eliminate the ‘tax bomb’, clients will have excess savings in a taxable account to use or invest as they please.

IDR plans are complex but offer many potential benefits to borrowers with Federal student loans. Thus, it is critical for advisors to understand the various rules around each plan to recognize when they might be useful for their clients carrying student debt. The benefits vary significantly, and depending on a borrower’s situation, IDR plans may not even make sense in the first place. But for some, using these plans will offer substantial savings over their lifetimes. Despite the uncertainty surrounding these repayment plans, they remain a crucial tool for planners to consider when assessing both a client’s current-day loan payments and the total cost of their student loan debt over a lifetime.